Farming Small

A story of a Vermont farmer whose relentless work eventually led to her leaving.

Click upper left photo for slideshow effect.

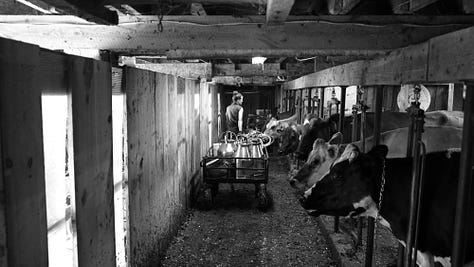

Her day starts at dawn and ends when everything is done.

But everything is never done on this small Vermont dairy farm. The days’ routine is relentless: Herd the cows into the barn, milk them by hand, pour the milk into the tank, set the fencing for the day’s and night’s grazing, herd the cows out, wash and sanitize the bottles, fill them, haul them over to the barn store, check on the cows, finish cleaning the parlor, sweep the barn, clean the manure, one last check of the cows. Home.

For about a year I’ve visited this small farm in Hinesburg, VT, where the young farmer, Aubrey, a wiry woman with a face that is both revealing and private, works every day to tend her 17 cows.

She is a good farmer if you accept my definition: A good farmer is one who takes good care of their animals.

Her cows live long lives. They are calm. They rarely make a sound. Only when a stranger comes into the barn do they tense up, but only a little; after a while they get used to him. To someone else.

The farmer knows what each produces; she tests the milk regularly. Because she sells raw milk. To the state of Vermont she, and others in the raw milk business, are outliers. So they have stringent requirements. Her herd’s milk is always, simply always, way better than the state requirements. She prides herself on that. She sells her milk through shares or drop-ins to the farm stand, a small room on the corner of the barn. She partners with organic vegetable farmers and natural meat producers and bakers and honey makers and candle makers to stock the store and give more incentive for people to drop in.

She does it alone. Occasionally her husband comes in — he works full time at a natural meat farm on salary — to clean out the barn with the tractor or to help her haul hay. But mostly she’s on her own. And she likes it that way. She shuns publicity saying, simply, “there are a lot of good farmers out there.”

She pays attention to what supplements the cows are eating, how much they are producing, the status of their pregnancies, the health of their hooves and hindquarters and udders. Each cow has a name, and she can tell you when she got it, where she got it or, lately, when it was born and by whom. She has a plan for the herd, for the breeding to improve the quality of the milk and its digestibility.

She had to put down the last of the original herd she had when she first bought the farm some eight years ago. “It was a sad day,” she said. I was there several weeks before it happened; the cow was struggling with a hoof that would not heal. There were other issues, too. So someone was brought in to kill her quick and humanely and she was buried deep in the woods.

Each day the young farmer gets up before dawn and heads down to the barn, out to the fields to bring them on in. She whistles to them, talks gently, lays her hand gently on their hindquarters when they begin to stray or slow down. When they’re in the far field — nearly a half mile away — she and the cows thread through the thick woods that separates the field and the barn. They know the way.

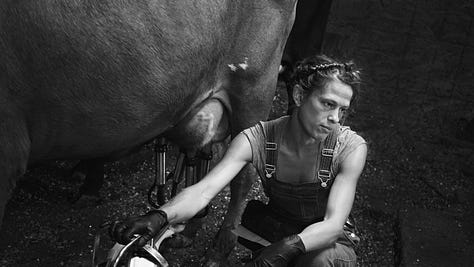

And she then milks them, one by one, disinfecting the teats, attaching the milker which sucks the milk into the milk can. Her only saving grace is that these cows are trained for one milking a day, not two.

She then hauls the milk cans to the parlor and pours the milk into the refrigerated tank, goes back and walks the cows out to whichever field they’re grazing at.

Returning to the barn, she washes the milkers, all the other equipment and then pours out the milk into the sterilized half-gallon Mason jars and carts the bottles to the refrigerators in the store.

She does this every day. Seven days a week. Fifty-two weeks of the year. Clear. Cloudy. Rainy. A blizzard. Below zero. 85 degrees and blazing sun. Every day. And she loves it. But it is wearing.

In the end, it wore on her for too long.

While Aubrey asked me to take these photographs — she’d seen my work on Instagram — she would never consent to my recording her, to formally interviewing her.

I asked her why. She said, “There are a lot better farmers out there than me.”

But there was something more to it. She was struggling mightily. I saw it — you can see it — in some of the photographs. A deep exhaustion. The ceasless nature of dairy farming was clearly taking its toll. She’d spent months unsuccessfully trying to find someone to assist her – and maybe eventually take over.

One day, as she was outside the barn store near the main road, her treasured new dog was hit and killed by a car.

So she decided to shut it down. She sold her cows and her equipment and left town. I didn’t even get a chance to say goodbye.

We miss her cows. We miss their milk. We miss Aubrey.

This is incredibly powerful, thank you for sharing this story, thank you for not hiding how hard it is to farm in this way and thank you for making such wonderful images. One of the very best things I have read on Substack.

I like this story very much! I felt an array of emotions reading this and viewing the photos.